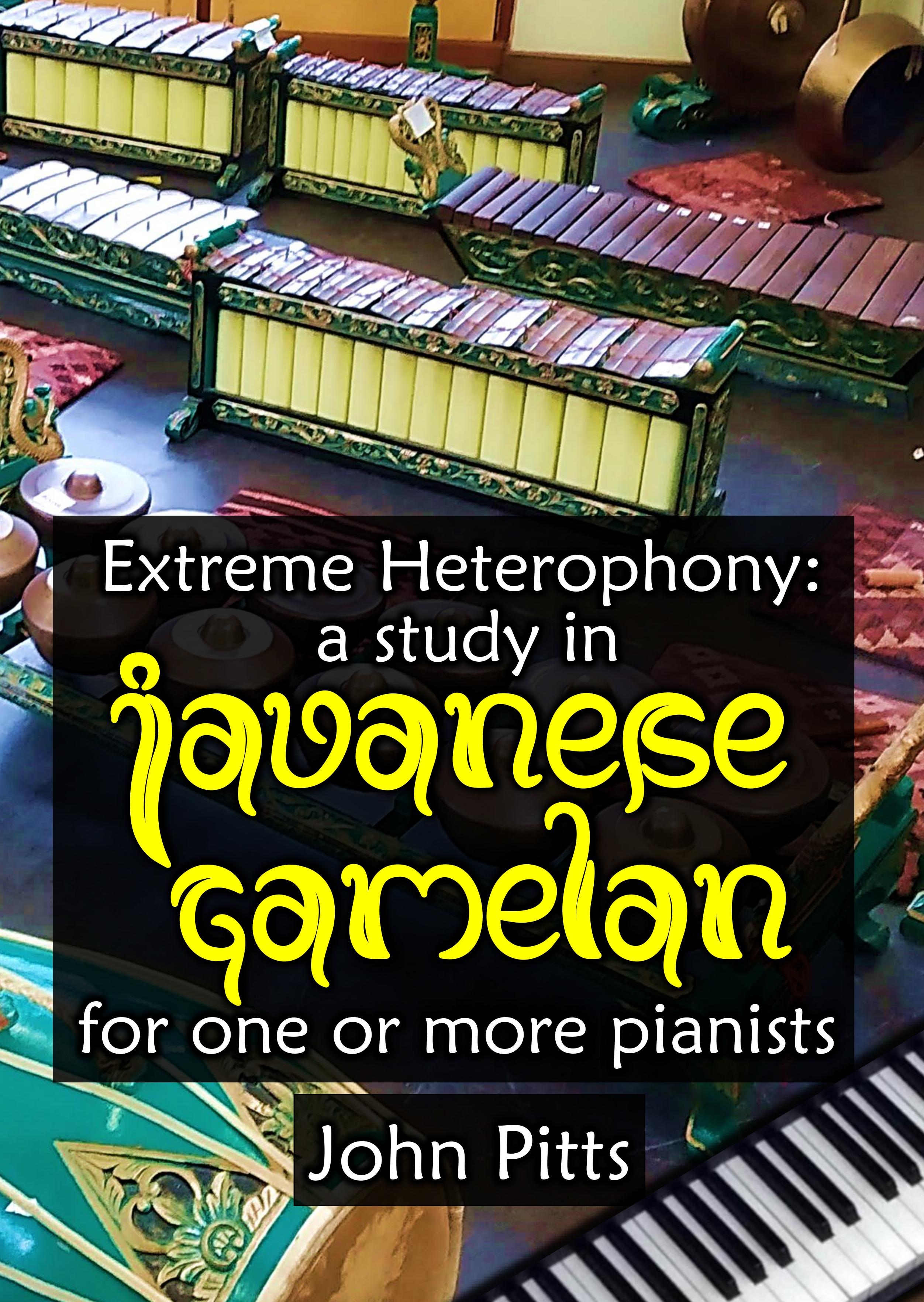

Today’s guest post has been penned by composer John Pitts, who has just published a new and fascinating book; Extreme Heterophony: a study in Javanese Gamelan for one or more pianists.

John has already written several books exploring Indian Raga Music, adapting it to the piano. In this new volume, he continues his exploration into the music of the Far East; the book is aimed at pianists experienced in western classical music who want to expand their musical experiences beyond the European canon and pop and jazz. In this article, John explains the publication’s background and content.

A new book for inquisitive pianists—either solo or in duets/duos/triets or multiple piano ensembles—to discover, step into, and explore music for gamelan orchestra from the Indonesian island of Java—what it is, how it works, and how to begin to play it.

Back in the Autumn 2020, having finished a major re-write of my book How to Play Indian Sitar Ragas on a Piano, I set my sights further east. Like many musicians, I knew of the existence of Indonesian gamelan music probably from a first introduction to its gongs and other tuned percussion instruments in school music lessons, and had listened to various recordings over the years. I’d had one fascinating experience playing on the set of Javanese gamelan instruments at Wells Cathedral School during my teacher training in 2003. As a composer I’d also done some tentative explorations, in 2014 writing a short prepared piano duet for the Danish/British duo Ingryd Thorson & Julian Thurber for a concert in the 2014 Samsø Piano Festival, Denmark, inspired by a particular type of Balinese gamelan—”Gamelan Balaganjur”. This translates as “Gamelan of Walking Warriors”, and has its origins in military music used in battle, now performed in Indonesia in competitions by large bands of dancing musicians with pitched and unpitched percussion. It is incredibly elaborate music with very little repetition, involving constantly changing speeds with layers of complex rhythmic gestures that require very impressive ensemble skill.

My real interest in actually ‘understanding’ gamelan really took off during the covid lockdown when I decided to properly find out what gamelan music actually is—i.e.: how it is constructed, how it works, what the notes are and why. I discovered, even with lots of resources, that this is a difficult task. There is lots of information available (in English) about the cultural contexts of performance, and the instruments and tuning systems etc., but as a composer I was after the notes themselves, the musical narrative, the logic for which notes are played, the musical gestures and journey created. I would have loved to have found the book I’ve just written—as it contains the stuff I wanted to know but failed to find easily (or at least decipher quickly) elsewhere. So this project was one of trying to find out and understand the basic musical grammar of gamelan music, and seeking to provide pianists with an accessible window into this extraordinary music, using appropriately comprehensible (and sensitively chosen) western terminology and staff notation. It came from a place of ever-increasing respect for a fascinating music that is well deserving of study, and profoundly different to any European/western music, or Hindustani ragas for that matter, or any other music from around the world that I’ve yet delved into.

Gamelan music can be broadly divided into regional varieties—Javanese, Balinese and Sundanese—and into numerous genres performed in a variety of contexts: concerts, theatre, wayang puppet theatre, dance, religious and secular ceremonies. I focussed on one such variety—Karawitan—the classical music of Central Java. Its ensembles consist of up to c.20 musicians on a range of tuned metal percussion and gongs, xylophone, plucked zithers, bowed string lute, bamboo flute, singers and drums. Almost every aspect of the music—including its core concepts, texture, metre, structures, sounds, tunings, scales, and aural tradition—is a world away from notated western classical music.

“Extreme Heterophony” in my book title refers to a foundational principle of how this music is constructed—akin to a theme and variations, but where c.10 types of related but widely diverse, decorative variations are all performed simultaneously—creating a rich, vibrant, exciting texture—and where the theme itself isn’t directly played. Many of these ‘variations’ or elaborations are part-learned, part-improvised within defined parameters. Gamelan musicians don’t generally use notation other than for the underlying ‘theme’ or ‘skeleton melody’ (the balungan), which they flesh out in real time according to learned ‘rules’ and patterns for their specific instruments. Some layers are independent of the pulse. For everyone else, the metre is end-weighted and beats are grouped with the notes leading into them—for newcomers extraordinarily counterintuitive. It is a profoundly different way of experiencing metre. It means that each player constantly looks forward and works out their style of elaboration in relation to the goal note on the 4th beat at the end of each group of notes in the theme.

In order to explore and elucidate the relationships between these multiple layers, I chose to do a deep dive into a single well-known composition in the central Javanese repertoire—Ketawang Puspawarna—composed by Prince Mangkunegara IV of Surakarta in the 1800s. Understanding the musical grammar of this piece should be a gateway to more complex pieces. I wanted to be able to understand the basic learned ‘rules’ of each layer well enough to be able to play them. Along with finding as much written material as I could, I listened to numerous recordings of different performances of the same piece, and transcribed and analysed representative sections of the different instrumental and vocal layers. This study allowed me to create several individual stand-alone (or perform-together) piano pieces. This had both an educational and artistic purpose. Each piano ‘piece’ demonstrates one or more layers from within the gamelan ensemble, and how the core theme (the ‘skeleton melody’) may be fleshed out by each player. They are intended to give interested pianists a performer’s insight into how this music is built, by being able to explore some of the intricacies of the musical construction of each instrument’s line—as far as it is possible on a piano—along with a downloadable backing track of gongs and drums (free to download). As gamelan music is fundamentally music for ensemble, each piano adaptation is designed to be played both on its own and also in any combination with any of the others—with multiple possible duet combinations (and a triet) at one piano, or duos or multiple-duets at two (or up to seven!) pianos.

My own experience is that playing through these different instrumental and vocal layers is really pleasurable—brain-engaging whilst also peaceful (the overall aesthetic is fairly peaceful), especially along with the backing track—and the exploration of the different manifestations of the same underlying melodic contour is intrinsically valuable and rewarding. I hope others will find this true for themselves. The thorny issues of using any kind of fixed notation, or of playing this music on the equally-tempered piano, are dealt with sympathetically—with the aim of providing a useful resource to pianists (and composers, improvisers and teachers) seeking to broaden their musical horizons in this enigmatic and alluring sound-world.

Purchase

Amazon.co.uk, Amazon.com and Amazon.ca or in bundles with other books (eg: How to Play Indian Sitar Ragas on a Piano) from here.  John Pitts

John Pitts

My publications:

For much more information about how to practice piano repertoire, take a look at my piano course, Play it again: PIANO (published by Schott Music). Covering a huge array of styles and genres, the course features a large collection of progressive, graded piano repertoire from approximately Grade 1 to advanced diploma level, with copious practice tips for every piece. A convenient and beneficial course for students of any age, with or without a teacher, and it can also be used alongside piano examination syllabuses too.

You can find out more about my other piano publications and compositions here.

from Melanie Spanswick https://melaniespanswick.com/2022/03/20/extreme-heterophony-a-study-in-javanese-gamelan-for-one-or-more-pianists-john-pitts/

No comments:

Post a Comment