Our meeting took place in Krefeld, at Kawai – the Japanese make of piano with which Alexander Gadjiev has become so familiar since his success at the Hamamatsu competition. Now his career is really taking off in Europe too: Gadjiev is a BBC New Generation Artist until the end of 2021 and is also one of the 25 chosen contestants at the upcoming 16th International Tchaikovsky Competition, 17-29 June in Moscow.

“At the competition in Hamamatsu I decided on a Kawai. I immediately felt at ease, and for me the best thing about Kawai is that, as a pianist, one can influence the sound itself. Playing legato, creating a mysterious atmosphere or rising to a grandiose climax: everything works, thanks to the exemplary way the mechanism functions.”

You were born in Gorizia, on the border between Italy and Slovenia, at a meeting point of peoples, cultures and languages.

Gorizia is just a small town, but the mixture of influences left its mark on me. Precisely because the town was so small and there was absolutely nothing by way of distractions, a few curious people had the opportunity to look inwards rather than outwards in their search for treasures. And that’s a central factor in developing an aesthetic that isn’t standardized, isn’t taught at high school – one that is born from inner compulsions rather than adhering to conventional rules. Moreover, my father taught an interesting class with many talented people, among them Giuseppe Guarrera, one of my best friends, who this year won a scholarship at the Klavier-Festival Ruhr.

Your father studied in Moscow.

Yes, under Boris Zemliansky, whose other pupils included Vladimir Ashkenazy and Alexander Toradze. At the heart of his teaching method was the development of a very personal way of thinking as an artist. At the root of it all was an extremely precise conception of the music’s character, a result of especially thorough study of the score – but also laying tremendous importance on the sound image: sound, sound quality, duration, colour and sound relationships were the main ways of achieving an ‘interpretation’ and opening up the listeners’ hearts. In addition, in his teaching, he demanded urgency and necessity, and empathy with the music while playing. After all, you don’t sit like a lump of stone at the piano, with everything carefully planned in advance; you ‘soperezhivat’’, as the Russians say – a big word that means roughly ‘live through something’. It’s very interesting to note how often people in those days used to compare musicians with actors (much more frequently than nowadays) and that some aspects of the Staniskavski method also found their way into music. Richter is perhaps one of the most important examples of such experiments.

Is that a key to the interpretation?

My intuition tells me how to play something. The analytical phase that precedes this is very interesting and informative, but in the end you have to go beyond that.

To turn the Bach/Busoni ‘Chaconne’ into a great narrative, for instance?

I’m very interested in science, and almost chose to pursue an academic career. Mathematics in particular appeals to me, because of the clarity with which you proceed from A to B. This inner logic is for example very strong in Beethoven and Brahms as well. But you can also achieve this in a mystical way. In a work with so many perspectives it isn’t easy to create a continuous line; I’ve worked hard on that. But you can give each variation its own character. Maybe you can experience this beauty most intensely in the concert hall, whereas you can grasp the rationale for the overall structure better on a recording.

Your expression is very personal but still remains close to the composer’s intentions.

Yes, but I also treasure Pletnev’s recording, who takes quite the opposite approach. He plays the piece like a free fantasy. This contrast is deeply rooted within me.

Richter and Horowitz are important for you, and they also embody a contrast.

I admire Richter for his spirit, his inner urgency and the compelling logic with which he plays. He’s one of the finest examples of the extra-musical in music. He follows not only the rules of music, the harmonic phrasing, but also a higher idea that encroaches and guides the entire interpretation – with grandeur, but also with a universal sadness. Horowitz was almost on the same level as composers. I think that’s what Rachmaninov meant when he said that nobody could play his Third Piano Concerto like Horowitz.

Compare that with Prokofiev’s Sixth Sonata as played by Richter. In both recordings you hear the primeval power, something frightening. Prokofiev also plays with death and doom in a grotesque manner. The logic and structure of his music are unequalled, he sheds new light on tradition, his melodic gift is almost as great as Mozart’s, and still you find this inexplicable inspiration. I feel that very strongly in Richter’s interpretations.

You also think very highly of Keith Jarrett – there’s a lot that’s inexplicable about him too.

He is one of my greatest inspirations. When I first got to know him, it almost seemed like a sin because up until then I had heard only classical music. I’ve heard him twice live, and it was fascinating to hear how his musical ideas had developed. At the same time it was also very exciting on a spiritual level. It’s great to see how someone makes a piece of music grow before your eyes, and in the process – just like you – hears the music for the first time. He started with nothing more than a single grain, and then you suddenly saw an incredible amount of blossom emerge. That is precisely what I feel when I listen to his recordings or concerts.

Shouldn’t it always be like that?

Most pianists today have a very rational approach. You see that everywhere in society nowadays, the urge to understand and to be productive. And that way there are probably many things that we don’t fully grasp. I also see it as the pianist’s duty to infuse a piece with new life.

Can music save the world and make people better, as Bernstein said?

Bernstein got that from Dostoyevsky, of course, but I do think it’s true. And it isn’t so complicated. Listening and making contact are a way of empathizing. And it isn’t a one-way street. For a pianist it’s an adventure that’s dependent on the audience, the hall, the instrument and the moment.

One person who seems to have wanted to eradicate that was Sokolov.

I have great admiration for his perfection, devotion and control. They say that he is immersed in the material 24 hours a day. For me he is an incredible architect… no, rather a film director. Every detail, every movement is planned in advance. I also find that scary. I think that for a surgeon for example, who must also be very concentrated and precise, Sokolov is the best. Horowitz suits me better. He’s more of an artist on stage, who transforms the energy of the moment. With him you feel the tension, the fear and the enormous vulnerability. He doesn’t play as if he was in his study. Richter had it too, the same quality, and it reflects inner richness, it has something mystical about it. It can’t be forced, and it’s difficult in our society, where we are almost compelled to be productive. But our opinions are simply a reflection of our own reality, and are 90% subjective.

Celibidache said that you can get to know yourself in music. Do you agree?

With Celibidache I admire the highest level of pure music. He was interested in the relationships between notes, cause and effect, structures. And yes, if you go to a concert with Bernstein’s words in the back of your mind, with awareness and sensitivity, then you can learn a lot about yourself. Then it’s one of the most beautiful things you can imagine.

Author: Eric Schoones

Photo credit with the KAWAI PIANO: © Hamamatsu International Piano Competition

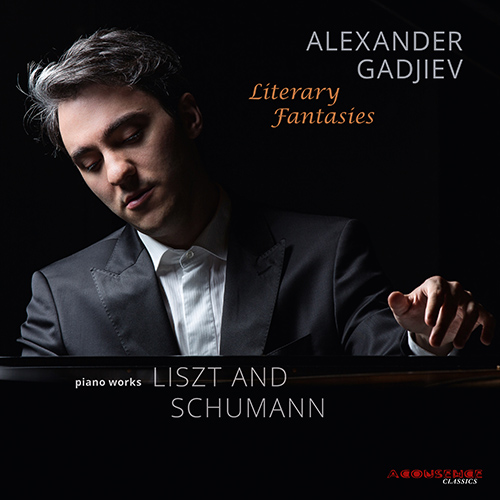

Most recent CD: Literary Fantasies

Liszt’s Three Sonnets of Petrarch and Après une lecture du Dante, and Schumann’s Kreisleriana and No. 2 of the Op. 111 Fantasiestücke.

Acousence Classics ACO-CD 13117

This feature is available for Gold members of pianostreet.com

Play album >>

‘I love literature. As Italians, Petrarch and Dante are close to each other and also to my own personality – therefore I understand the undertones that you might otherwise miss. The Dante Sonata is a very modern piece. Liszt is the inventor of the soundtrack. In it you can really hear hell and love.’

— Alexander Gadjiev

This article is a contribution from the German and Dutch magazine Pianist through Piano Street’s International Media Exchange Initiative and the Cremona Media Lounge.

Pianist Magazine is published in seven countries, in two different editions: in German (for Germany, Austria, Switzerland, Luxemburg and Liechtenstein) and in Dutch (for Holland and Belgium).

Pianist Magazine is published in seven countries, in two different editions: in German (for Germany, Austria, Switzerland, Luxemburg and Liechtenstein) and in Dutch (for Holland and Belgium).

The magazine is for the amateur and professional alike, and offers a wide range of topics connected to the piano, with interviews, articles on piano manufacturers, music, technique, competitions, sheetmusic, cd’s, books, news on festivals, competitions, etc.

For a preview please check: www.pianist-magazin.de or www.pianistmagazine.nl

from Piano Street’s Classical Piano News https://www.pianostreet.com/blog/articles/alexander-gadjiev-to-save-the-world-9853/

No comments:

Post a Comment